White Tea Defined By Industry

This article is from the Tea & Coffee Trade Journal (Apr '06). This publication contains many interesting articles on both tea and coffee. It is a great place to learn about tea and the growing regions.

By Barry Cooper

There is a form of Camellia Sinensis that reigns as one of the world’s greatest teas, and that is white tea. Recently, it has experienced a surge of interest and demand that has propelled the grade into the forefront of tea news. Yet, little is really known about this unique product.

|

What is white tea?

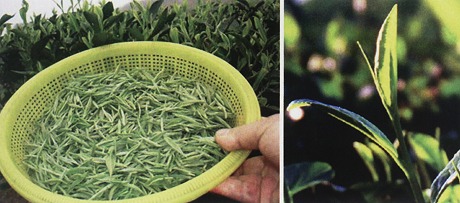

Answer: It is the bud of the tea bush, then perhaps the bud and one leaf, or maybe the bud and two leaves, which will then depend on the season it was picked and the country of origin. Then again, not all tea producing countries can make white tea.

If all of this sounds confusing, let me add to that confusion by saying that what is true is that white tea was first harvested during the Song Dynasty (960-1279) in the Zhenghe, Jianyang, and Fuding counties of the Fujian province. It is also one of the rarest and most expensive teas in the world. However, if this is so, then why are there boxes on sale for fewer than five dollars? Well, if it’s too good to be true, then it probably isn’t all white tea in the box.

Then, what is the standard for white tea? There isn’t one, and that’s the problem

The Tea Association of the U.S. thought it would be a good idea to establish a definition to protect the integrity of one of the world’s great teas. They conducted a survey among their sister associations to help define the white tea segment. Responses came from around the globe with three organizations strongly in favor of a traditional definition, two leaning in that direction, one suggesting we stay out of the fray, and 11 favoring a new definition that ‘white tea’ should be a process, as opposed to an origin.

Here are the growing pains of a ‘category.’ Currently, there are 600-800 metric tons of white teas produced each year worldwide. The Fujian province can increase production to 3000 metric tons within two years, and of course, other countries can produce ‘white teas’ as well.

Everyone is looking at white teas’ potential, but no one likes the price or availability. Consistency and seasonality are also an issue. When buyers need small quantities of white tea, this is not a problem. Trouble begins when buyers notice the large market potential and start marketing blended white teas. This is easy to do, as the public does not understand the category.

This is then the inherent danger for white tea, since poor quality whites, and greens sold as whites, will damage the reputation and longevity of the category.

The board of the U.S. Tea Association concluded that as an industry we should agree as to what defines white tea, and stick to it. They felt that packers should be open about blended products, as well as specify the contents of a white tea “blend.” They also agreed that packers should be responsible for the claims made and be able to substantiate health and wellness claims, which may have not been corroborated.

The

first step, according to the U.S. Tea Association, was to give white tea a definition. Despite being first produced in Fujian province, white tea

refers to the production technique, not a statement of origin. It is produced from the fresh unfurled buds of the Camellia sinensis shrub and the

processing involves no withering, fermentation or rolling process. The resultant liquors should be clear to pale yellow in color.

The

first step, according to the U.S. Tea Association, was to give white tea a definition. Despite being first produced in Fujian province, white tea

refers to the production technique, not a statement of origin. It is produced from the fresh unfurled buds of the Camellia sinensis shrub and the

processing involves no withering, fermentation or rolling process. The resultant liquors should be clear to pale yellow in color.

Among the current countries producing “white tea” are China, India, Kenya, Sri Lanka and Vietnam. But caveat emptor -- or buyers beware --- be sure to satisfy yourself as to the method of production and be careful to understand the “real” potential availability. If the liquor is green, it is a green tea and more importantly, if it is cheap tea, it probably isn’t white tea.

Finally, if in doubt, turn to the following proposed definition.

In Order for White Tea to Be Termed So, It Should Be:

Processed in accordance with the strict harvesting and processing guidelines, which were originally established in Fujian Province, China.

Lower grades (Pai Mu Dan, Kung Mei, Sow Mei) are made from larger and coarser leaves, but the process is the same and there should be some presence of the white buds.

There should be no withering, fermentation (oxidation) or rolling of the buds, though the process of air-drying by definition involves some withering and oxidative effects.

Silver Needle grade is made from finely plucked tender shoots (buds) of Camellia Sinensis usually, but not always, from the first flush after winter. These are air-dried or directly warmed/fired.

The liquor of White Tea is a very pale yellow color and mild tasting in the cup. Coarser and cut grades are of course less pale and delicate than the highest grades (Silver Needle).

Any tea producing country may make white tea, provided manufacturing conforms to the above harvesting and processing steps. The value of this tea depends on the proportion of buds included, the leaf appearance, as well as liquor quality and color (the paler and more buds included in the leaf, the better).

It is said, “Guidelines are for the wise men and the obedience of fools.” I guess I can add to that by saying, “Don’t be fooled. Be guided.”

I would like to recognize Peter Goggi of Unilever Best Foods, John Snell of Van Rees, Jem McDowall UTTC and Joe Simrany of the US Tea Association for their time and energy in bringing this project home. It is a team effort and I was just the one asked to write the article. Thus, the blame for the content and comment is mine, other than the definition of course, for which everyone can claim credit.