Tea arrived in seventeenth-century Europe at a time of burgeoning exploration and trade, and caused a revolution in drinking habits and gave rise to a number of social institutions such as the tea garden and the ritual of afternoon tea. It wasn't long before tea became a necessity of daily life, so the utensils needed to prepare and serve tea became essential as well.

Colonial Americans quickly adopted the taste for tea and valued fine silver for their homes to serve this important beverage. American silversmiths emulated English and Continental styles.

The practice of tea drinking arrived with colonists from both England and the Netherlands and was already established by the mid-seventeenth century, evidenced by the number of tea wares recorded in household inventories. The earliest of these were undoubtedly imported from abroad, but American silversmiths began producing teapots by the start of the eighteenth century. At first globular or pear-shaped, apple-shaped teapots became the norm by the mid-eighteenth century. By the later decades, drum- and oval-shaped pots with straight spouts reflected the preference for Neoclassical design

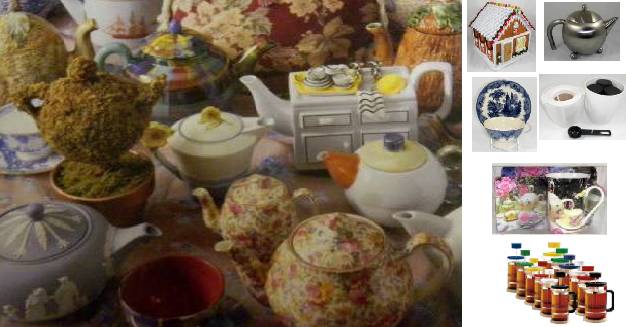

In addition to the pots from which these beverages were poured, additional vessels in the equipage included covered sugar bowls, creampots, teakettles, and hot-water urns. Canisters for the dried tea leaves, sometimes made in pairs, and salvers or trays for serving were also occasional accompaniments. Matching services did not appear until the 1790s.

In the 1760s, the British government began to impose a tax on tea, first through the Stamp Act of 1765 and later with the Townshend Act of 1767. Dissatisfied colonists took to smuggling tea or drinking herbal infusions. Outraged merchants, shippers, and colonists staged a number of demonstrations, culminating in the famous Boston Tea Party of December 1773. Paul Revere's ride and the first shots fired at Lexington were but a year and a half away.

Political hostilities were in due course resolved, and Americans gathered once again around the tea table. Moreau de Saint-Méry, a foreign visitor to Philadelphia in the 1790s, noted the warmth and hospitality of these events. "The whole family is united at tea, to which friends, acquaintances, and even strangers are invited."